How This Feels

It’s a rainy Saturday in Washington, DC, and it is just a few days from my 41st birthday and about ten days from the date of my surgery.

I have been in better moods.

Last evening, as I was eating dinner with my wife, I sat rather silently, and at one point I just told her that I am really, really sad.

Conveying sadness about physical injury, perhaps particularly when that sadness is attached to a very personal kind of athletic endeavor, is an exceedingly difficult thing to do. If I told you that my father just died—he hasn’t, thankfully—you would, I’m sure, be able to empathize with that loss. However, if I tell you that I’m incredibly sad abut the possibility of never completing another marathon, you might likely turn to smarm. It could be worse, you might find yourself saying. Another of my favorites: marathoning is overrated.

You might even be inclined to fashion yourself a doctor, arrogantly proclaiming that running is bad for us anyway—after all, isn’t my ankle problem the direct result of running?—while citing some random internet article you read one time that said something about running and knee pain.

I have always been inclined to tell people that running is the only thing that I am good at, and I believe this to be true. The other successes that I have had in my life—completing graduate school, sustaining a teaching career, learning how to develop websites (?)—have only come through tenacious, dogged effort. College was incredibly difficult for me, graduate school, particularly at the MA level, was even more difficult, and writing remains an exceedingly challenging, painstaking, and exhausting task, which is one of the reasons why my scholarly output is so meager (which is also why I have failed at being an actual academic).

It has never been that way with running. I am certainly not the fastest guy in town, but I am one of the faster guys in town, and I have always been able to, well . . . just run, with very little effort or preparation.

I have qualified to run the Boston Marathon three times. I got kind of a delayed start with marathon training, not really making a concerted attempt at it until somewhere around 2012. Finally, in March of 2014, I officially raced my first marathon at the Shamrock Sportsfest in Virginia Beach. The weather was terrible—I believe there was a gale warning at one point—and my pacing was not great. Still, I finished, just sneaking under my qualifying standard. As a result, I achieved one of those famed qualifying times that was officially a “BQ,” as the jargon goes, but was not fast enough to get me a number.

So, in 2015, I trained harder—smart, for sure, but harder nevertheless. I ran two marathons that year, the New Jersey Marathon and the New York Marathon. I ran Boston qualifying times in each of those events, meeting the steepest qualifying standard in one of them.

I was in the best shape of my life at the end of 2015, and I was fast.

Eventually, though, my good fortune ran out, as is inevitable for all athletes. I got hurt in late December of 2015, and I never quite recovered. Mostly, I lost my bearings, and I think I just got pulled into the cycle of trying to come back from injury too quickly, and I spent the better part of 2016 and 2017 with a variety of stress reaction problems. Also, this osteochondral defect of mine, which had been living quite comfortably in my foot for some undetermined period of time, started becoming symptomatic and frustrated all of my attempts to get back into shape.

As a result, I was never able to make use of any of my Boston Marathon qualifying times.

That hurts, my friends.

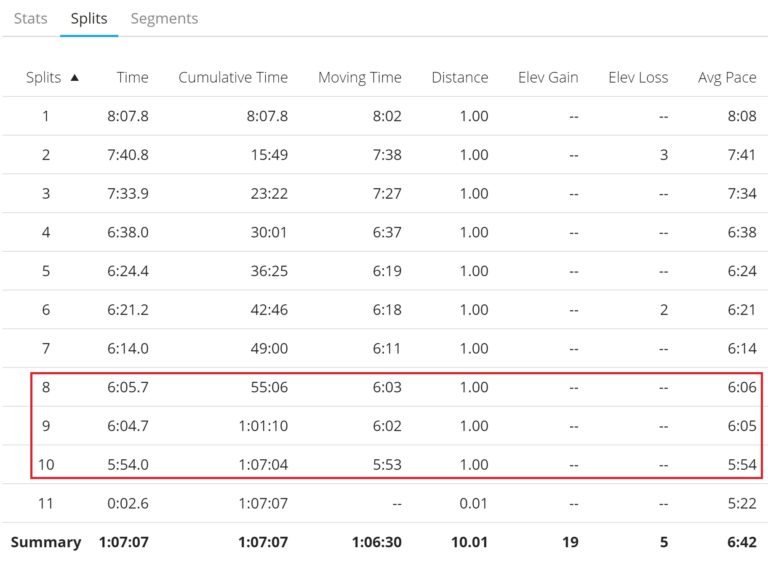

Right before my 2015 injury, I completed the last significant workout of my running career to date. If you are at all close to me, you have heard about this workout, because I talk about it like an accomplishment that is somewhere around the same level as the moon landing, which is annoying, I know. On December 21, 2015, I finished a full day of work, and I went out for my routine weekly pace run. It was a gorgeous December evening—dark, yes, but temperate, the perfect conditions for an efficient ten-mile workout.

I remember quite clearly rolling into the tenth and final mile of the workout, cruising along the Potomac River, the lights of the city to my north. I was travelling home in a few days for the Christmas holiday, and I just felt like everything was exactly as it should be. This is how it is supposed to feel, I remember thinking. This—the ease with which my legs carried my body lightly and quickly down the bike path—is exactly how I had always wanted to feel.

I haven’t felt that way since.

I have been fortunate enough to work with very good doctors throughout the process of diagnosing and treating my current ankle injury. They are humane people, and they respect my dignity and my athletic aspirations.

But they have told me, in the kindest of ways possible, that my marathoning days might be behind me, which means that I might never run the Boston Marathon. My ankle, they tell me, will never be perfectly repaired—cartilage does not grow back—and I will most definitely be at an increased risk for future dysfunction and potentially more significant complications.

Best case scenario: it will be multiple years before I would even be in a position to attempt another marathon completion, which is also a hard pill to swallow. I am only (almost) 41, and I feel really, really old. My body really does feel like it is failing me.

Working in disability, I know that health is always contingent and that disabling conditions are a fact of human existence. At the same time, I have always felt that disability activism has been rather uncaring in the context of acquired disability, whether temporary or permanent, and particularly within the context of competitive athletics.

James Berger was instrumental in my early academic work on disability, and he remains central to my thinking about the process of aging. Though I understand the disability is not something that is shameful (or that should be the subject of pity), I cannot state things more simply that this: I do not want my body to act this way. I have very specific running goals, and I want to achieve them. I cannot, at this moment, intellectualize this feeling of deep loss and personal grief.

My body is always in motion. Moving is how I understand myself. You never slow down, my wife routinely tells me.

In just under two weeks, I am electively submitting myself to a restorative procedure that will, in very significant ways, immobilize me for a long period of time. Despite the nearly daily pain that I am currently experiencing, I do not want to do this. I do not want to have to go through this.

I want to run, but I can’t, and that hurts, and I am sad.

And that is how this feels.

–October 27, 2018